I think what you're getting to is Wittgenstein's

family resemblance, and I think you may be onto something.

Also, I should point out the notion of academics in a bubble is pejorative. It means they're out of touch. There's a reason the number one piece of advice we give to beginners is to join a local club. Notwithstanding, I suppose you could draw an analogy to an ascetic living alone in a cave in search of enlightenment. I guess it's a tradeoff.

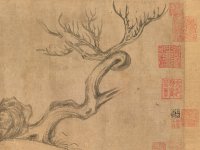

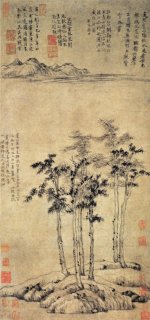

I'll give you and example of the "bubble" thing. If you have ever been around biblical scholars, OT guys are normally super limited on their "expertise" on the NT texts and vice versa. It's extreme specialties with concepts and jargon understood within the community and if you want to swim in their pond, you have to take your own swimming lessons many times. Also some of the artists in the pictures that I posted were loyalists of one Dynasty and when the next crew came in they became fugitives often resorting to a live as a monk in the high mountains and from that came the art. It can be taken as pejorative I guess but it's also true if you've been around them and from this came the term "ivory tower", which while pejorative is somewhat descriptive. I recall the difficulty of preparing a sermon that parishioners would actually care about after grad school. I was so used to the (forgive the bluntness) "mental masturbation" of grad school that making things practical became difficult.

My overall point was that, in general terms a "master" (not me by any definition) would understand the "essence" of a "literati bonsai" but likely not be able to put it into a bullet point definition. Allow me expand on that a bit:

Let's compare and contrast two bonsai styles in terms of two philosophical schools of thought. First, let's start with a formal upright, (chokkan). It has an extremely specific definition from which, one cannot diverge without breaking the style. This style is rather Aristotelian in nature as it is empirical, categorical, rule-bound. You can teach this style through explicit instruction and evaluate success against measurable criteria.

On the other hand we have literati or bunjin style bonsai which exist more in a Platonic school of thought. For him, Forms were the perfect, abstract ideals, the "chair-ness" of all chairs, the "beauty" behind all beautiful things. Physical objects are imperfect shadows or participations in these eternal essences. You can't point to the Form itself; you can only recognize its presence in particulars through reason and intuition. Literati bonsai operates similarly. There is no checklist. No prescribed trunk angle, no required number of branches, no specified pot shape. What exists is an essence, a feeling of elegant struggle, austere loneliness, scholarly defiance of convention. You recognize a literati tree the way you recognize melancholy in music, not by measurement, but by resonance with an ideal that exists somewhere beyond the physical specimen. So you can say at the end of the day that it is "defined" by what it "evokes" rather than what it "contains". Sure it has generally agreed upon elements:

- Sparse, not lush

- Tall and reaching, not grounded

- Imperfect, not symmetrical

- Suggestive, not declarative

I would say it returns us to were we started in this discussion with your Justice Potter Stewart quote. Thus as

@Michael P suggested, go work on your trees and create something that "evokes" the feeling you are after. If successful, call it literati (it may very well fit into another more literal (see what I did there) category as well) . Truth be told, your own personal definition that you started in the beginning is quite functional in my opinion.